Aside from his painting of the Primavera, Sandro Botticelli’s other greatest work, done for the Medici family, is the Birth of Venus. Unfortunately, we do not know for sure which Medici it was painted for, or which location it was originally hung in.

Before considering the subject matter, it is important to take note of the medium. This is a work of tempera on canvas. During this time, wood panels were popular surfaces for painting, and they would remain popular through the end of the sixteenth century. Canvas, however, was starting to gain acceptance by painters. It worked well in humid regions, such as Venice, because wooden panels tended to warp in such climates. Canvas also cost less than wood, but it was also considered to be less formal, which made it more appropriate for paintings that would be shown in non-official locations (e.g. countryside villas, rather than urban palaces).

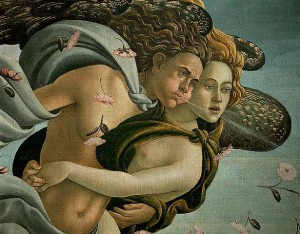

The theme of the Birth of Venus was taken from the writings of the ancient poet, Homer. According to the traditional account, after Venus was born, she rode on a seashell and sea foam to the island of Cythera. In the painting we see here, Venus is prominently depicted in the center, born out of the foam as she rides to shore. On the left, the figure of Zephyrus carries the nymph Chloris (alternatively identified as “Aura”) as he blows the wind to guide Venus.

The theme of the Birth of Venus was taken from the writings of the ancient poet, Homer. According to the traditional account, after Venus was born, she rode on a seashell and sea foam to the island of Cythera. In the painting we see here, Venus is prominently depicted in the center, born out of the foam as she rides to shore. On the left, the figure of Zephyrus carries the nymph Chloris (alternatively identified as “Aura”) as he blows the wind to guide Venus.

On shore, a figure who has been identified as Pomona, or as the goddess of Spring, waits for Venus with mantle in hand. The mantle billows in the wind from Zephyrus’ mouth.

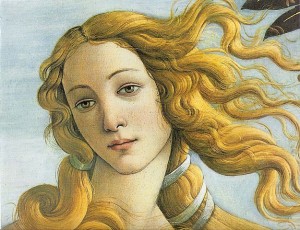

The composition is similar in some respects to that of the Primavera. Venus is slightly to the right of center, and she is isolated against the background so no other figures overlap her. She has a slight tilt of the head, and she leans in an awkward contrapposto-like stance.

Botticelli paid much attention to her hair and hairstyle, which reflected his interest in the way women wore their long hair in the late fifteenth century. He gave Venus an idealized face which is remarkably free of blemishes, and beautifully shaded her face to distinguish a lighter side and a more shaded side.

Botticelli paid much attention to her hair and hairstyle, which reflected his interest in the way women wore their long hair in the late fifteenth century. He gave Venus an idealized face which is remarkably free of blemishes, and beautifully shaded her face to distinguish a lighter side and a more shaded side.

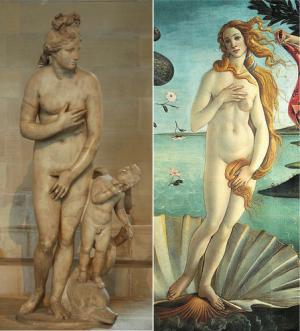

Of obvious importance in this painting is the nudity of Venus. The depiction of nude women was not something that was normally done in the Middle Ages, with a few exceptions in specific circumstances. For the modeling of this figure, Botticelli turned to an Aphrodite statue, such as the Aphrodite of Cnidos, in which the goddess attempts to cover herself in a gesture of modestly.

In painting Venus, Botticelli painted a dark line around the contours of her body. This made it easier to see her bodily forms against the background, and it also emphasized the color of her milky skin. The result of all of this is that Venus almost looks like her flesh is made out of marble, underscoring the sculpturesque nature of her body.

Comparison of the Capitoline Venus (after the Aphrodite of Cnidos) with Venus from Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus”.

The demand for this type of scene, of course, was humanism, which was alive and well in the court of Lorenzo d’Medici in the 1480s. Here, Renaissance humanism was open not only to the use of a pagan sculpture as a model, but also a pagan narrative for the subject matter.

Although the Birth of Venus is not a work which employed Renaissance perspectival innovations, the elegance of the classical subject matter was something that would have intrigued wealthy Florentines who patronized this type of work. However, it would not have appealed to everyone, like those who viewed the worldly behavior of the ruling Medici family as corrupt or vile. By the 1490s, the tension that resulted from the clash between courtly excess and those who wanted religious reform came to a climax when the preacher Savonarola preached his crusade to the people of Florence. One of the people influenced by the preacher was Botticelli, whose change of heart moved him to destroy some of his early painting by fire.

I am confounded by analyses of Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” that describe the art as depicting “chaste,” “pure,” “scared,” or “divine love.” How can that be when Venus is conspicuously displaying a labia just above her hand? Is it possible that this masterpiece is Renaissance pornography?

That, I think you’ll find is her thumb.

The problem with such an analysis, as I see it, is that 1) Botticelli took the trouble to place Venus figure within the context of the classical myth, and 2) her depiction seems to be different from gratuitous/base works of the time period. If Botticelli wanted to depict a scene which appealed to the base instincts, why bother to be discreet about anything?

Great analysis. Helped me with my art exam 🙂 Thank you

How do I cite this website, no information is presented to do that.